From roughly 1990 to 2020, electricity markets operated in what could be called the “flat load era” — marked by slow, stable demand growth and a centralized, fuel-based generation mix. But since 2020, the landscape has shifted dramatically.

Drivers of this shift include: a surge in data center development, the push toward electrification of vehicles, buildings, and industry, and the rapid growth of intermittent renewable resources

During that same span of 30 years, some states began to change their electricity identity, converting from monopoly states, where vertically integrated utilities manage generation, transmission, and distribution, to competitive states where generation and supply are open to private investment and consumer choice.

With more than three decades of two different electric markets, it bears asking the question: which market structure is proving more capable of meeting this new wave of demand?

The data points to one clear answer: competitive electricity markets are outperforming monopoly states on resource adequacy, generation growth, and investment responsiveness.

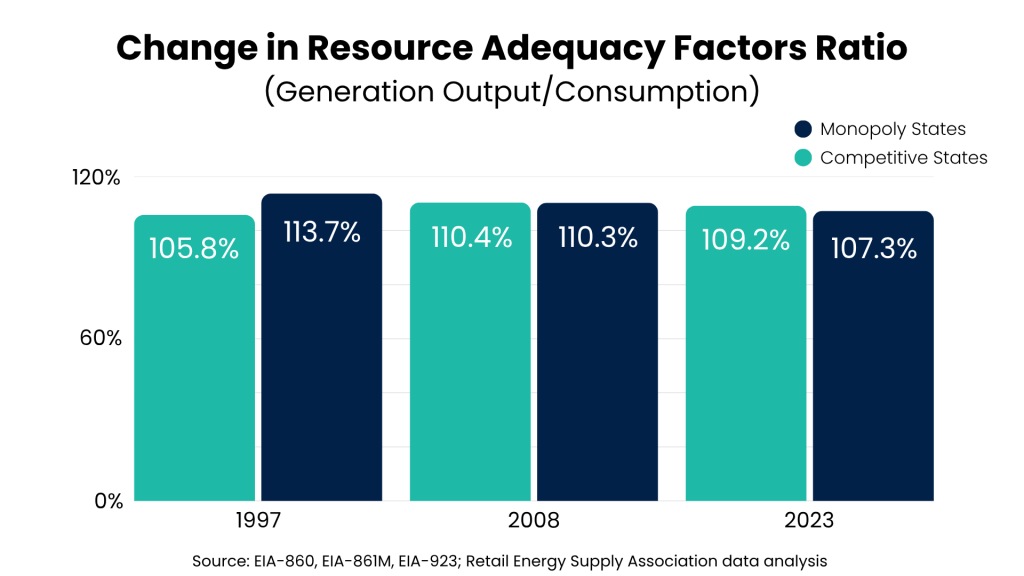

As of 2023, competitive states now produce more electricity relative to their consumption than monopoly states — a complete reversal from 1997, when monopoly states generated around 8% more than competitive states.

Competitive states, such as Pennsylvania, are successfully serving as a net exporter of electricity, supporting load growth with generation growth. Additionally, competitive states are excelling at keeping price increases low or even better than before introducing competition. This shift underscores how competitive markets are better equipped to address today’s emerging demands facing electricity markets.

One major advantage of competitive markets is their ability to attract private capital when it’s needed — without relying solely on ratepayer-backed investments.

Utility companies in monopoly states that have been caught flat-footed through the flat load era, unable to see the change in energy demand ahead, are faced with an immense challenge of securing more power without financially harming their customers. This is also happening at a time when utilities were preparing to retire outdated baseload generation resources.

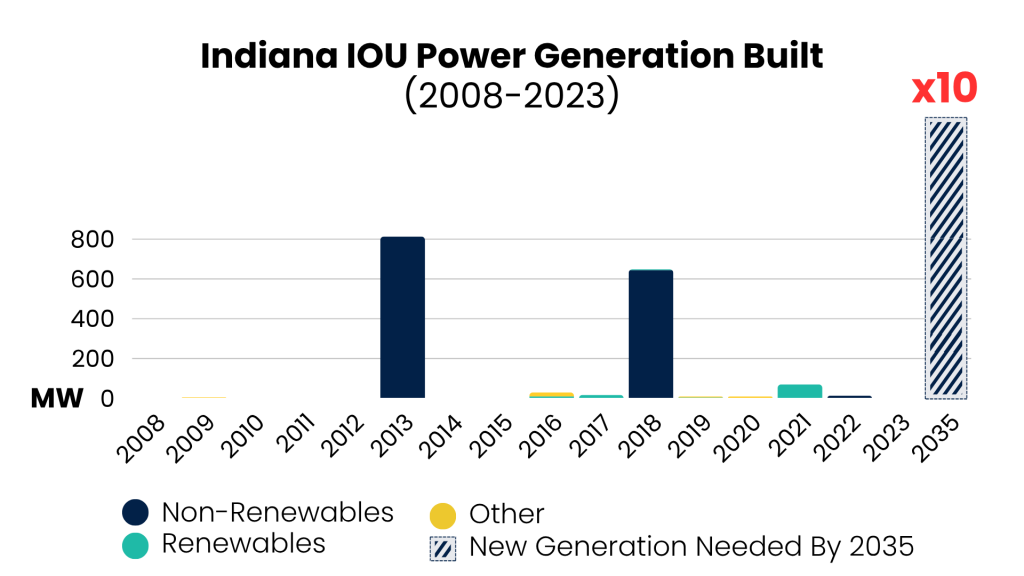

Take Indiana, for example. This is a state that is expecting 40% of its generation to be retired by 2035, while also expecting to see more than a 50% increase in demand. Using Lazard’s Levelized Cost of Energy report, it will cost –– conservatively –– $17 billion to build 22 new natural gas plants just to meet the projected 15,000 MW of new power generation needed by 2035.

Without private investment from competition, all $17 billion would be passed down to ratepayers through charges on their bills. This is after utility rates have already increased by 60% over 16 years –– and during that time, only less than 2,000 MW of new or updated power generation was built or completed.

But in states where competition is welcomed, private investments are made by energy companies to build new and efficient power plants, protecting all ratepayers from exorbitant and burdensome costs. Consumer classes can then ensure the security of more energy resources and shop for their supply at more affordable prices.

Rapid growth in serving electrification and data centers, successful generation, and resource adequacy are paramount to market success.

As the U.S. grid transitions into a new era of complexity, the ability for consumers –– especially large energy users –– to procure their own electricity creates a diverse energy grid that is more reliable, more responsive, and more resilient. This approach for achieving a stronger grid protects ratepayers from the burdensome costs of utilities billing for the buildout of new power plants.

Sources: Information used in this blog includes data that was sourced from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, utility integrated resource plans (IRP), FERC Form 1, and Lazard’s 2025 Levelized Cost of Energy report.